This is a course on Coursera, taught by Barbara Oakley, and Dr. Terrence Sejnowski. The course comprises four modules that introduce how our brain functions, along with several very useful learning techniques applicable to all disciplines, not just STEM. The insights from the course are based on solid research from neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and contributions from leading instructors and practitioners in various fields. It is a general learning-focused course with a lifelong impact on many people.

Content

- What is Learning?

- Chunking

- Procrastination and Memory

- Renaissance Learning and Unblocking Your Potential

What is Learning?

Thinking Modes

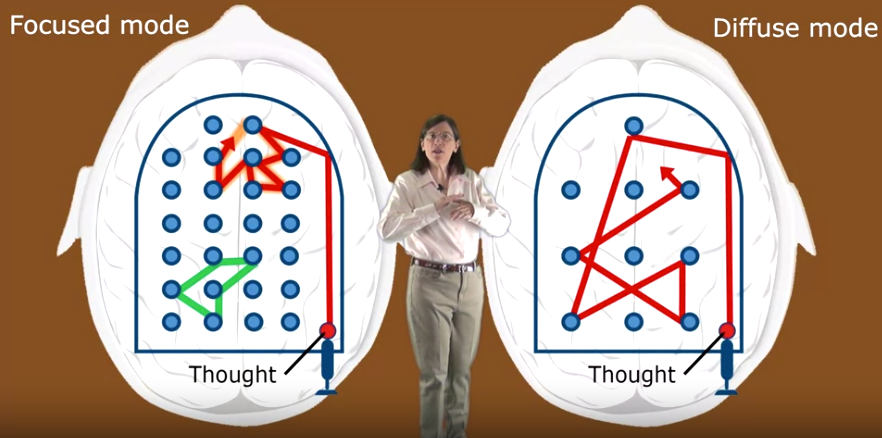

Researchers found that we have two fundamentally different modes of thinking:

- Focused mode

- Diffuse mode

Focused mode, as its name suggests, is a mode that is activated when we concentrate intently on something that we are trying to learn or understand.

Diffuse mode, on the other hand, turns out to be a relaxed thinking style

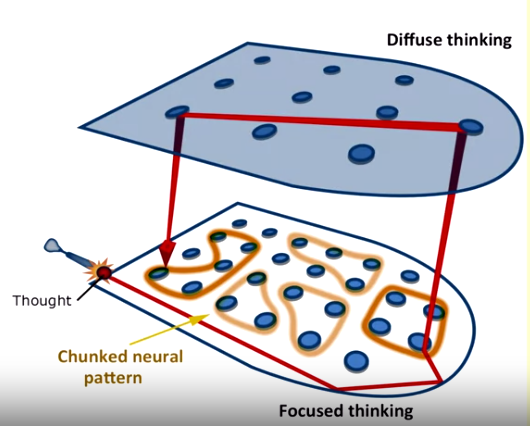

An analogy of the pinball game can be used to help us understand how these two different modes function.

On the left, it shows the focused mode. The orange pattern shown at the top represents a familiar thought pattern, such as adding some numbers. Using this mode, we are able to solve problems and understand concepts that are related to something we are rather familiar with. However, when it comes to innovation and creativity. This mode of thinking cannot be of much help. That’s when the diffuse mode plays its role.

The diffuse mode, as shown on the right, can help us look at things broadly and make new neural connections traveling along new pathways.

It is worth noting that two thinking modes are mutually exclusive, which means we cannot reside in both modes at the same time. However, it is possible to transfer from one to the other.

Procrastination and the Pomodora Technique

Procrastination is natural and common. When people look at something that they really would rather not do, they activate the areas of their brain associated with pain. In reaction, the brain will try to stop the negative stimulation by switching attention to something else. That is the cause of procrastination.

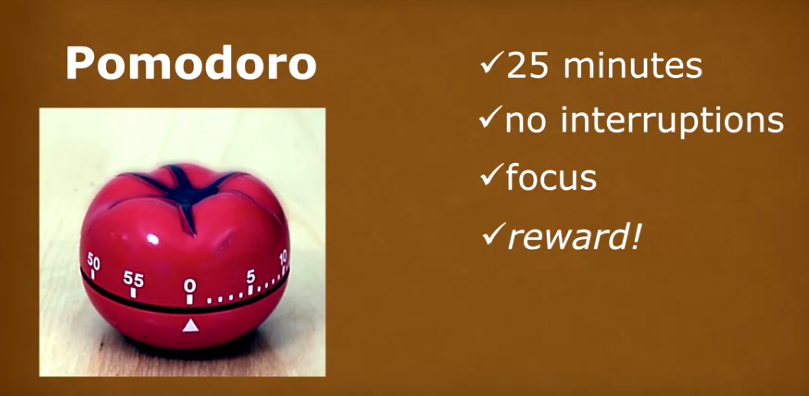

However, researchers found that not long after people start actually working on what they didn’t like, the neurodiscomfort disappears. Based on this fact, a mental tool called the Pomodoro can be effective in helping us tackle procrastication. All it involves is a 25-minute focus period without any interruption, followed by a 5-minute break (to change your focus for a while). Keep in mind that a 25-minute focus is effective for most people, but not everyone. Some people may find a longer time period of focus suits them better (e.g. 50-minute focus + 10-minute break).

Memory

There are two major memory systems:

- Short-term memory (aka working memory)

- Long-term memory

Working memory is like an inefficient mental blackboard. It’s centered in the prefrontal cortex and deals with what we’re immediately and consciously processing in our minds. Repetitions are needed in order to keep things in working memory.

Long-term memory is like a storage warehouse, distributed over a large area. Different kinds of long-term memory are stored in different regions of the brain.

Practice and repetition help move information from working memory into long-term memory.

However, there’s also a trick to repetition. A technique called “Spaced Repetition” is useful and efficient. The idea is to space the repetition out and repeat it over a number of days. Research has shown that repeating something 20 times in one evening is far less effective than practicing it the same number of times over several days.

The importance of sleep in learning

Sleep is important in learning, in a few aspects.

Being awake generates toxic byproducts in our brain, and sleep plays a crucial role in eliminating these poisons.

Persistently getting too little sleep over an extended period can be associated with adverse conditions such as headaches, depression, heart disease, diabetes, and a higher risk of premature death.

During sleep, our brain tidies up ideas and concepts. It erases less important ideas and strengthens areas that we need or want to remember. It also consolidates our memory into easier to grasp chunks.

It’s effective to review what we’ve learned right before we take a nap or go to sleep for the evening. Dreaming about what we’re studying can substantially enhance our ability to understand.

Chunking

What is a Chunk?

Chunks are compact packages of information that our mind can easily access. Building chunks can help establish a solid knowledge foundation for a challenging discipline.

Chunking is the process of uniting bits of information together through meaning. It helps our brain to run more efficiently. Simply remembering something without understanding it does not help build up chunks.

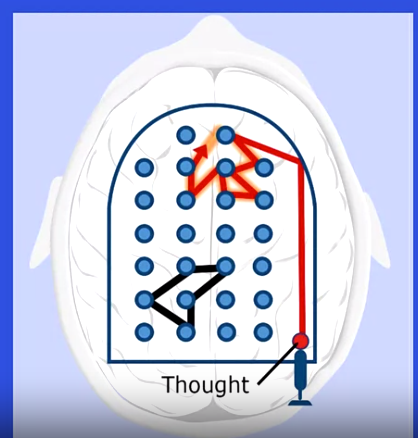

When we’re focusing attention on something, it’s as if we have an octopus in our prefrontal cortex to help make connections to information. When we are stressed, the octopus begins to lose the ability to make connections. This explains why our brain does not work correctly when we’re angry, stressed, or afraid.

Learning a new language is like embedding basic words and patterns (chunks) so we can speak freely and creatively.

The first step towards gaining expertise in academic topics is to create conceptual chunks that unite information through meaning. The same technique can also apply to music, sports, dance, and literally every subject.

A chunk means a network of neurons that can fire together so we can think of a thought or perform an action smoothly and effectively.

Focused practice, spaced repetition can help create chunks.

How to Form a Chunk?

The best chunks are the ones well ingrained that we do not have to consciously think about connecting the neural pattern together. That’s the idea of making complex ideas, movements, or reactions into a single chunk.

When learning math and science, we bear a heavy cognitive load when we’re first trying to understand how to work out a problem. Then, we often divide it into a walk-through example. However, this sometimes blocks us from understanding the connection between steps; instead, it may focus on thinking about why an individual step is taken.

Here are the basic steps behind how to make a chunk:

- Focus our undivided attention on the information we want to chunk, staying away from interruptions.

- Understand the basic idea we’re trying to chunk. Understanding is like super glue that helps hold the underlying memory traces together. However, we can still create chunks if we understand a concept and do not relate it to other materials we’re learning. But those may turn out to be useless chunks that our brain may find difficult to retrieve later on. This usually happens when we simply take what a teacher presents but do not review it soon after we first learn it. Testing ourselves is an effective technique to speed up our learning. We truly understand something when we can actually do it.

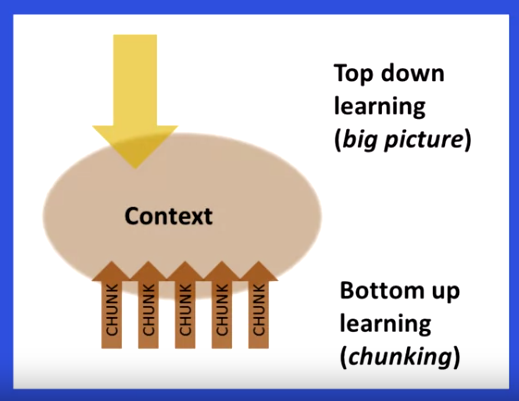

- Gain context so we can see not just how but also when to use this chunk. It means going beyond the initial problem and seeing more broadly. Repeating and practicing with both related and unrelated problems in different contexts can help us understand when and when not to use a chunk. As an example, we may have something in our toolbox, but if we do not know when to use it, it’s simply useless. Learning takes place in two ways: top-down and bottom-up. The bottom-up chunking process builds and strengthens each chunk so we can easily access them. The top-down process allows us to see what we’re learning and where it fits in. A tip for reading a book is to do a rapid walkthrough of a chapter before we begin studying it.

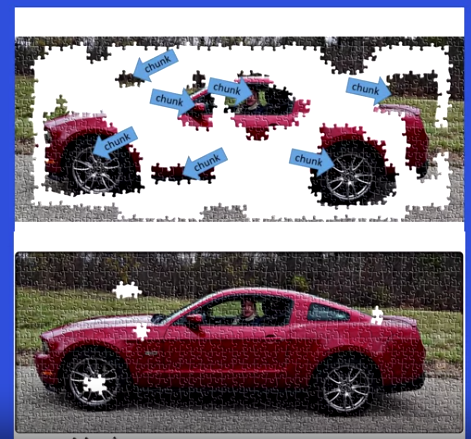

Another tip is to learn the major concepts or points first, then the details. As the following puzzle shows, we can solve the puzzle by grasping the main ideas of how this car is built, and then we can fill in the puzzle pieces. Even though a few pieces are missing, we can still see the big picture of the car.

Recall

Psychologists have shown that rereading a book is much less productive than recall: after we’ve read the material, simply look away, and recall it. By practicing and recalling, we can learn far more and at a much deeper level than using any other approach.

The retrieval process itself enhances deep learning and helps us to begin forming chunks.

Recalling material when we are outside our usual place of study can also help strengthen our grasp of the material, making us independent of cues from any one given location.

Illusions of Comptence

Merely glancing at a solution and thinking you truly know it yourself is one of the most common illusions of competence in learning.

Highlighting and underlining can sometimes be ineffective and misleading, fooling us into thinking that we’ve internalized the concept. It’s advisable to understand the main ideas before making marks and to keep underlining or highlighting to a minimum, focusing on one sentence or less in a paragraph.

Testing ourselves is an effective technique to eliminate illusions of competence. It helps ensure that we truly understand and have retained the information we’ve been learning.

Making mistakes is also valuable. Mistakes not only reveal areas for improvement but also play a crucial role in correcting our thinking, helping us learn and perform better.

Neuromodulators

Neuromodulators are chemicals that influence how a neuron responds to other neurons. Three of them are important to learning:

- acetylcholine: focused learning

- dopamine: reward learning, decision making, motivation

- serotonin: diffuse mode, social life, risk taking behavior

The Value of a Library of Chunks

Gradually building the number of chunks in our mind is a key strategy to enhance our knowledge and gain expertise. It allows us to organize information effectively, making learning more efficient and facilitating a deeper understanding of complex subjects.

Chunks can help us understand new concepts. When we grasp one chunk, we often find that it can be related to similar chunks, even in very different fields. This idea is called transfer.

The diffuse mode can play a crucial role in connecting two or more chunks together in new and innovative ways, enabling us to solve novel problems and approach challenges with a fresh perspective.

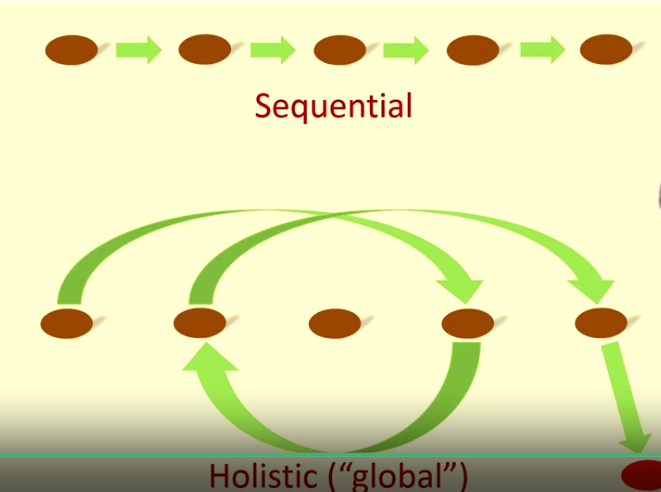

There are two ways to problem solving:

- Seqential: step-by-step reasoning, focus mode

- Holistic intuition: linking of several seemingly different thoughts, diffuse mode

Most difficult problems and concepts are grasped from the diffuse mode.

Law of Serendpity:

Lady Luck favors the one who tries.

Overlearning

Continuing to study or practice after we’ve mastered what we can in the session is called overlearning. Research has shown that overlearning can be a waste of valuable learning time.

Repeating something that we already perfectly know can also create the illusion of competence, giving us the false impression that we’ve mastered the full range of materials, when, in reality, we may have only mastered the easy components.

Deliberate practice is a technique to focus on the more difficult material, to help avoid the illusion of competence in this scenario.

Einstellung

Einstellung is a phenomenon where our initial, simple thought, an already existing idea, or a neural pattern prevents a better idea or solution from being found. It highlights how pre-existing mental frameworks can sometimes hinder the exploration of more innovative and effective solutions.

Interleaving

Interleaving is a technique involving jumping back and forth between problems and situations that require different techniques or strategies. It’s a useful method to overcome Einstellung, allowing for a more flexible and adaptable approach to problem-solving and learning.

Interleaving is extraordinarily important and it helps us to learn more deeply. It builds flexibility and creativity.

Moreover, interleaving between different disciplines can enhance our creativity even further. This cross-disciplinary approach encourages the brain to draw connections between diverse fields, fostering a more innovative and creative mindset.

Procrastination and Memory

Tackling Procrastination

Goot learning is a bit-by-bit activity.

Procrastination is easy to fall into. Willpower is hard to come by, and shouldn’t be wasted on fending off procrastination except when necessary.

Procrastination is a bad habit that influcences many important areas of our life.

Procrastination shares features with addiction.

Inner Zombies

The routine habitual responses our brain falls into as a result of specific cues.

Habits

Habits have four parts:

- The cue: the trigger that launches us into the zombie mode, it has four categories:

- location

- time

- how we feel

- reactions

- The routine: the zombie mode

- The reward

- The belief: we need to change the underlying belief in order to change a habit

Process versus Product

It’s normal to begin a learning session with a few negative feelings.

Another key to prevent procrastination is to focus on process, instead of product. Process involves the flow of time, habits and actions associated with that flow of time. For example: I’ll spend 20 minutes working. Product, on the other hand, is an outcome. For example: a homework assignment that we need to finish.

Processes relate to simply habits, which means that we can utilize the zombie mode to help us get into the flow of time. Our inner zombie likes processes.

The pomodoro technique mentioned before is a powerful tool to help us focus on process.

Harnessing Zombies

The trick to overriding a habit is to change our reaction to the cue. The only place where we need to apply willpower is in changing our response to the cue.

Back to four components of a habit, from the perspective of getting rid of procrastination:

- The cue: We can prevent most damaging cues by distancing ourselves from distractions, such as turning off the cell phone or staying away from the internet.

- The routine: Our brain falls into the zombie mode when we’ve gotton the cue, this is why we need to rewiring our old habit. The key to rewiring is to plan and develop a new ritual.

- The reward: Only when our brain starts expecting a reward, will the important rewiring take place that will allow us to create new habits. For example, we can stop all tasks at 5:00 pm.

- The belief: We should believe that we can change our procrastination habit.

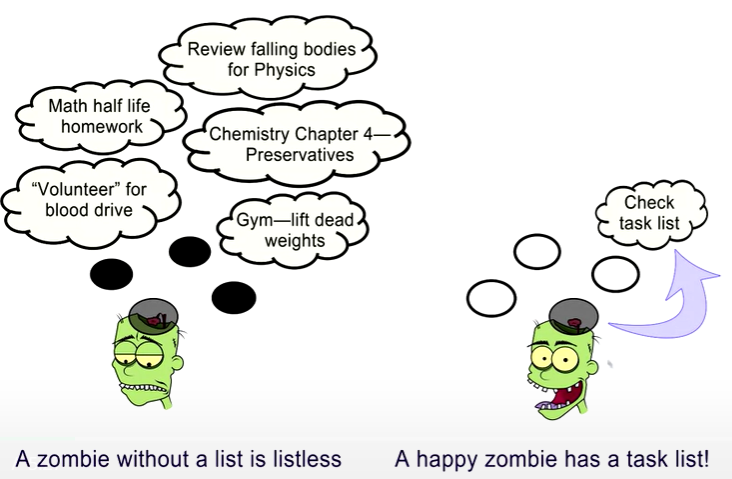

A good way to keep perspective about what we’re trying to learn and accomplish is planning well. Specifically, we should have:

- Weekly list of key tasks

- Daily TODO list

We should write the daily task list the evening before the day starts because it helps our subconscious grapple with the tasks on the list, allowing us to figure out how to accomplish them. This is where we can utilize the ‘zombie mode’ to help us overcome procrastination.

Another tip is to eat your frogs first in the morning. Try to work on a most important and most disliked task first, when the day begins, for at least one pomodoro, if not completing the entire task.

Memory

There are a few tips to build solid long-term memory:

- Use lively visual metapohor and analogy

- Spaced repetition and practice

- Use the Memory Palace technique

Renaissance Learning and Unblocking Your Potential

How to Become a Better Learner

There are two tips to become a better learner:

- Physcal exercise: It helps new neurons survive, and is by far more effective than any drug on the market today to help us learn better. It benefits all vital organs, not just the brain.

- Practice makes perfect: Only when the brain is prepared. Practice can train the brain.

The Value of Teamwork

When working in focus mode, it’s easy to make minor mistakes in our assumptions or calculations. The intense focus often leads to a desire to cling to what we’ve done.

Teamwork is one of the best ways to catch our blind spots and errors.

Collaborating with friends or teammates who share a focus on the same subject can help us identify where our thinking has gone astray.

They serve as a larger-scale diffuse mode outside our brain, capable of catching what we may have missed or cannot see. Furthermore, explaining concepts to peers can deepen our understanding of the subject.

Test Taking Tips

Taking tests is a crucial component in consolidating our knowledge.

A few useful tips on testing taking:

- Start with hard and jump to easy: This can help activate the diffuse mode of thinking.

- Get excited

- Take deep breaths to relax when feeling stressed or fearful.

- Don’t let your brain deceive you. This is when the focus mode enforces a sense of attachment, making us believe we are on track when, in reality, we may be totally off course. Switching to the diffuse mode is helpful in this scenario.

A Test Checklist

Every time before a test, go over the following checklist and see whether our preparation for test-taking is on target. The checklist is developed by educator, Richard Felder. It’s suitable for many disciplines.

- Did you make a serious effort to understand the text?

- Did you work with classmates on homework problems?

- Did you attempt to outline every homework problem solution?

- Did you participate actively in homework group discussions?

- Did you consult with the instructor?

- Did you understand all your homework problem solutions?

- Did you ask in class for explanations of homework problem solutions that weren’t clear to you?

- A study guide?

- Did you attempt to outline lots of problem solutions quickly?

- Did you go over the study guide and problems with classmates and quiz one another?

- A review session?

- Did you get a reasonable night’s sleep before the test?